JWST Sees Red with First Pictures of Mars

Sanje Fenkart, a science communicator and freelance journalist, is the new editorial assistant for the CERNCourier. She took part in the media internship programme at the Europlanet Science Congress (EPSC) from 18-23 September 2022 funded by the Europlanet 2024 Research Infrastructure (RI) project. Here she reports on results presented at the meeting.

Read article in the fully formatted PDF of the Europlanet Magazine.

Since the start of its scientific mission in June, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has impressed the astronomical world by taking images of the far-away Universe with unprecedented resolution and detail. Recently the telescope – a joint project by NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) – has shifted its focus to our next-door neighbour, Mars.

Earth’s ‘little sibling’ is a rather photogenic fellow, observed by amateurs, public observatories, professional ground-based and space telescopes. Since 1964, there has been a constant trickle of probes, satellites, landers and rovers, which explore the Red Planet.

While these robots send us close-ups from a familiar yet strange world, it’s worthwhile taking a look at Mars with a telescope – even one in your backyard.

JWST is designed to look primarily at faint objects such as exoplanets as well as the first (and oldest) stars and galaxies in space. In order for them to be captured, JWST is equipped with very sensitive instruments, which allow it to collect as much light as possible.

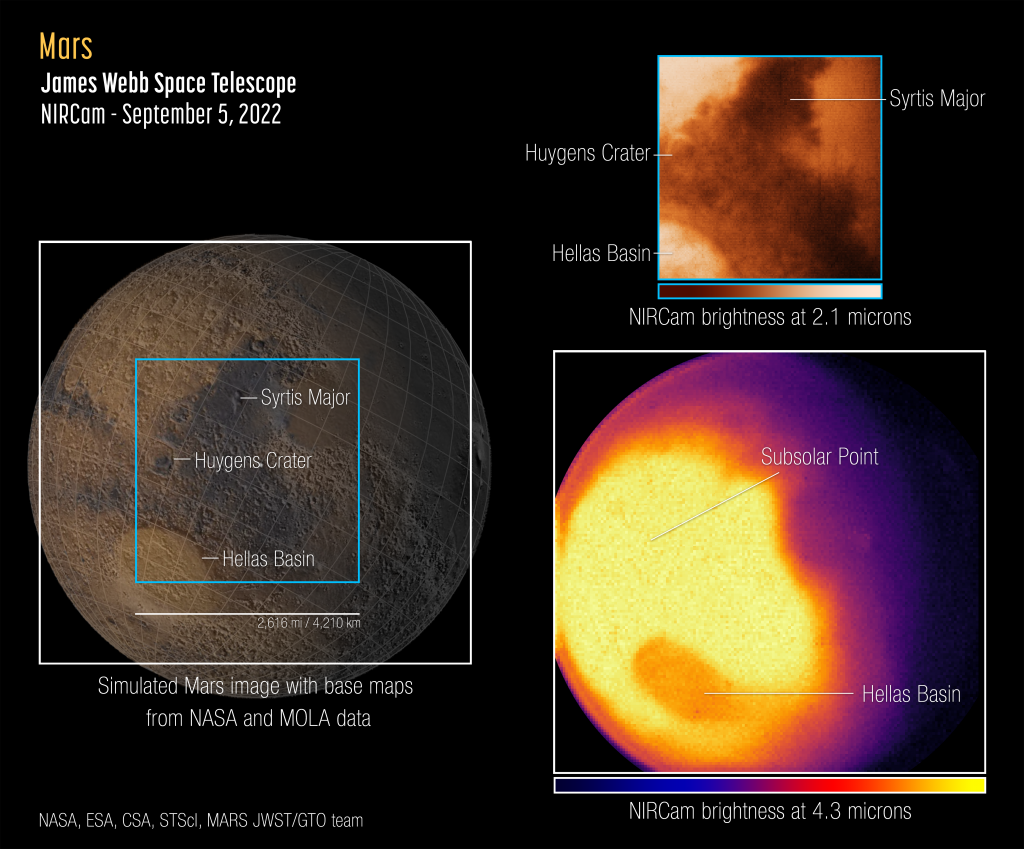

Mars, however, is close by and very bright – nearly too bright for JWST. Fortunately, a team of international scientists, led by researchers from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, has been able to collect and edit spectroscopic data into valuable pictures (right). The Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) managed to take snapshots of Mars’s surface at two different wavelengths using two of the instrument’s 29 filters.

A zoomed-in picture shows different features on the surface like craters, volcanic rocks and properties of the coating of dust. A second image shows a heat map that marks brighter and darker regions, depending how much heat is given off. As expected, the polar regions are cold, as is the shadowed night-side, which is delineated with a distinct ‘terminator’ (the border between day and night). Towards the equator, where the Sun is shining almost full-on (at 2pm Martian time), the heating results in an overly bright spot. Curiously, the hottest part exhibits a darker patch; this coincides with an impact structure called “Hellas Basin”, which has a depth of over 7,000 metres (>23,000 feet). Within the basin, the pressure changes considerably from top to bottom and consequently affects the atmosphere, leading to the dark feature spotted by JWST.

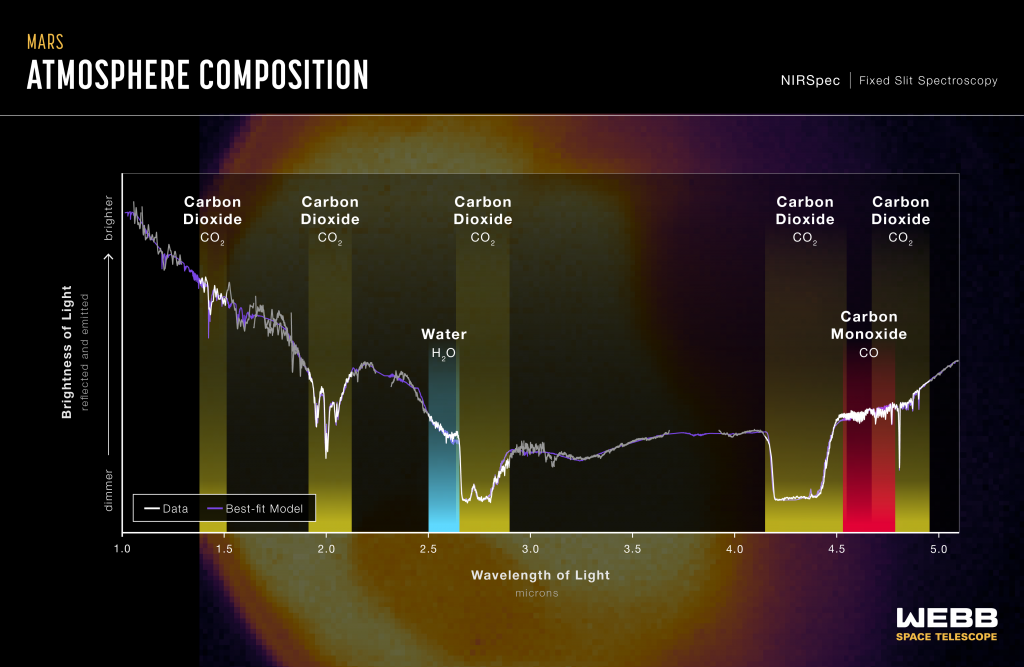

Switching instruments, the Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) has documented Mars’s atmospheric composition (left). These first results were obtained during Guaranteed Time Observations (GTO) and they look promising. NIRSpec found an abundance of carbon dioxide (CO2), alongside water (H2O) and carbon monoxide (CO).

However, what scientists are really looking for is methane (CH4). On Earth, methane is one of the most prominent tracers for living organisms, a so-called ‘biomarker’. Organisms like us, microbes and plants all produce methane. The planet itself can outgas methane if it has geological activity. So far, methane has been found only in the slightest of traces on Mars, with its origin – and even existence – still under discussion.

In these first JWST spectra, there were no new results on the methane abundance. However, JWST will look at Mars many times in the future – whenever an observation window opens – and the spectrograph’s capabilities should be able to find even the slightest whiff of it.

Find out more about JWST observations of the Solar System and of exoplanets in Issue 3 of the Europlanet Magazine.