Finding New Ways of Envisioning Venus

Jörn Helbert (DLR) looks forward to three new missions to investigate Earth’s mysterious twin.

Read article in the fully formatted PDF of the Europlanet Magazine.

Venus is our next-door planet. It’s almost identical in size to Earth and yet we know so little about it. It has been visited by the European Space Agency (ESA) Venus Express mission from 2006-2014 and the Japanese mission, Akatsuki, is still in orbit there. But otherwise, it has been really neglected in terms of missions. This has always been puzzling to me, because I have a long list of things that we don’t know about Venus.

We have been fighting to get missions to Venus for a really long time – I’ve been involved with the VERITAS mission concept for 12-13 years and in iterations of EnVision for a similar length of time. It’s really exciting to have three missions now selected. The new interest in Venus has partly come through discussions with the exoplanet community about why their models always lean towards Earth-like planets. They’ve asked for fundamental parameters for Venus to improve their models, like the composition, or what’s on the surface of Venus, and we just don’t have the answers. So people have finally realised that we need to find out more about this planet that has evolved in such a different way from the Earth.

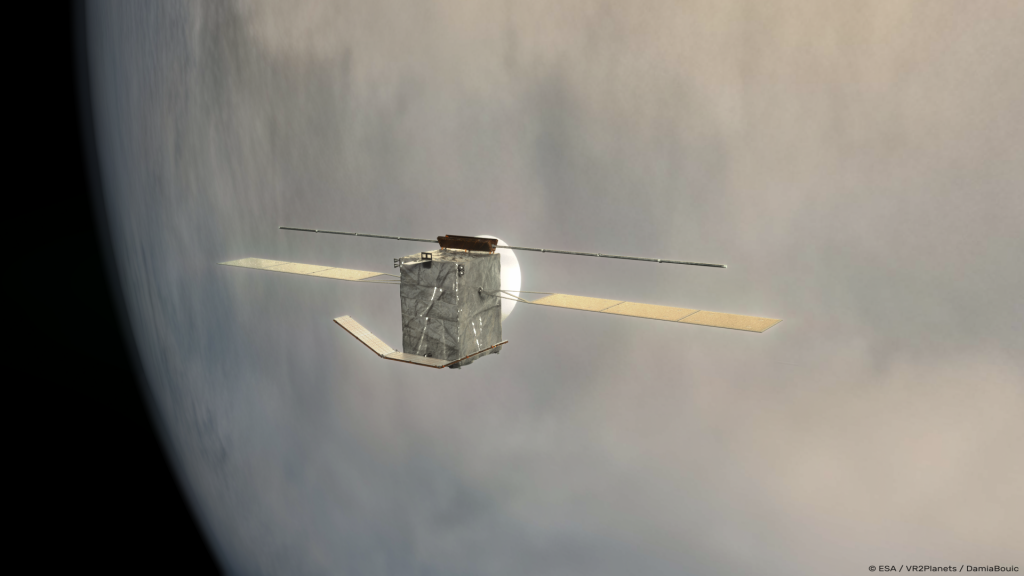

Venus Express was mainly an atmospheric mission. When our team at DLR first proposed that we could use a really small wavelength range around one micron to see the surface, I had the impression that no one really believed much would come out of it. In the end we were very successful and made some real advances for surface science at Venus, to a degree that people were not expecting. Through Venus Express, we demonstrated that we could measure the surface composition of Venus from orbit in a way that does not require landers, and I think this helped us with the selections earlier this year by NASA of the VERITAS mission and by ESA of EnVision (due for launch in 2028 and 2031 respectively).

However, the instruments on Venus Express were never really designed for the surface observations that we made, so we had many limitations. We could show there were variations on the surface – this region looks different from that region – and that there has been volcanism in the recent geological past of Venus. But we couldn’t actually be sure what we were looking at. The problem was that we were looking on the night side of the planet from orbit to see the infrared glow from the surface through the clouds. Even though the surface is really hot – 450 degrees – it’s a very tiny signal to detect. And because it was a strange, new technique, there were no laboratory measurements to help us interpret the data.

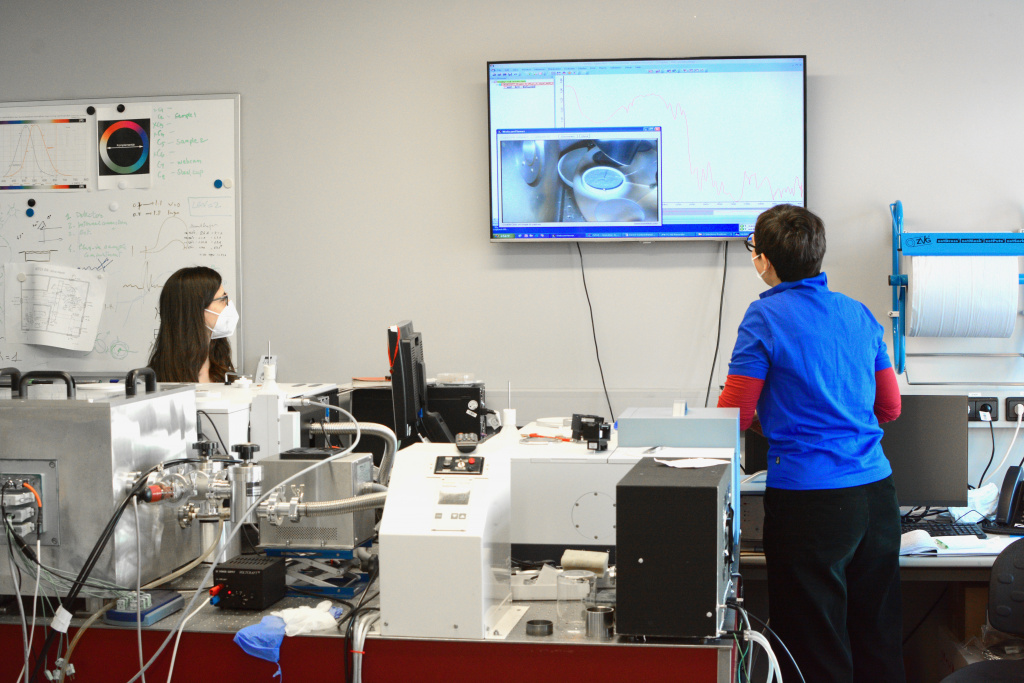

So, triggered by Venus Express, we set up a laboratory in Berlin, supported by funding from Europlanet 2020 RI, that allowed us to do measurements in the exact range of one micron. Combining these experimental results with Venus Express data, we were able to show that it’s possible to learn a lot about the surface of Venus from orbit. That allowed us to say that now is the time to go back there with this new technology, and to propose instruments that are now both on EnVision and VERITAS.

We have already built a prototype of the instrument that we want to fly, to show that it works in principle. We are now in the detailed planning phase to get from this prototype to something that will fly to Venus on the spacecraft, with all the testing and steps that are involved to do that.

It’s particularly interesting, because we are doing this for two missions at the same time. We have the experience of working with teams from NASA and from ESA, which both have slightly different approaches. Because EnVision, VERITAS and the DaVinci+ Venus decent probe (due for launch in 2029) have all now been selected, our teams are not in competition anymore. So we can come together and think how we can collaborate to help each other: VERITAS will go first, and VERITAS data will help make EnVision better.

On the other hand, it’s been challenging to get through the study phase of a mission with the Covid-19 situation. Everyone has been working from home and could not travel. It’s a strange situation working with people I’ve only seen on screen, and never actually met in person. Hopefully, this will change and we can soon meet face-to-face.

The Planetary Spectroscopy Laboratory (PSL) at DLR in Berlin can be accessed through the Europlanet 2024 Research Infrastructure (RI) Transnational Access Programme. PSL provides reflection, transmission and emission spectroscopy of samples from ultraviolet to far infrared. Simulation chambers are available for emissivity measurements: from 0.7 to 200μm under vacuum for in a temperature range from 320-900 Kelvin, or under dry air from 290-420 Kelvin.

The development of the PSL Venus Chamber received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 654208 (Europlanet 2020 RI).

Interview with Jörn Helbert at EPSC2021:

Banner image credit: ESA/VR2Planets/Damia Bouic.