First results from Cheops: ESA’s exoplanet observer reveals extreme alien world

Monika Lendl and Kate Isaak will be available to answer questions from the media during a dedicated webinar hosted by the Europlanet Science Congress (EPSC2020) at 15:00-15:30 CEST today (28 September).

Join here with the following credentials

Webinar ID: 895 0008 3953

Webinar Passcode: 488568

ESA’s new exoplanet mission, Cheops, has found a nearby planetary system to contain one of the hottest and most extreme extra-solar planets known to date: WASP-189 b. The finding, the very first from the mission, demonstrates Cheops’ unique ability to shed light on the Universe around us by revealing the secrets of these alien worlds.

Launched in December 2019, Cheops (the Characterising Exoplanet Satellite) is designed to observe nearby stars known to host planets. By ultra-precisely measuring changes in the levels of light coming from these systems as the planets orbit their stars, Cheops can initially characterise these planets — and, in turn, increase our understanding of how they form and evolve.

The new finding concerns a so-called ‘ultra-hot Jupiter’ named WASP-189 b. Hot Jupiters, as the name suggests, are giant gas planets a bit like Jupiter in our own Solar System; however, they orbit far, far closer to their host star, and so are heated to extreme temperatures.

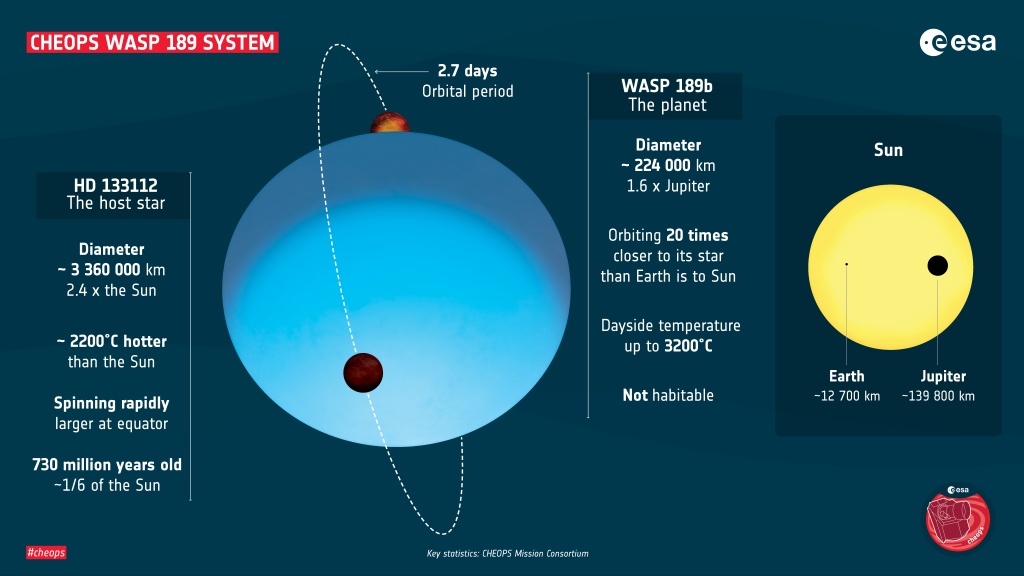

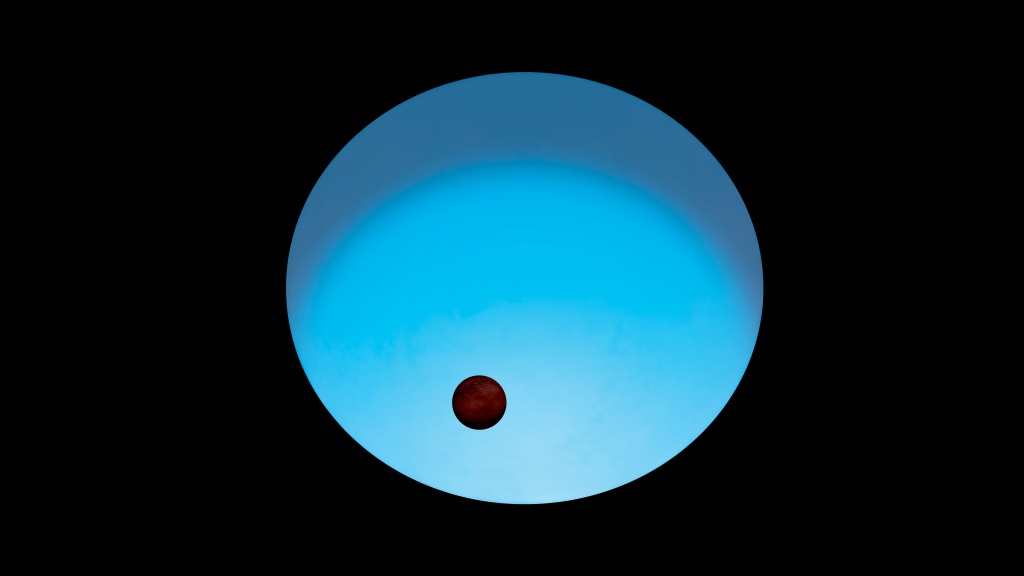

WASP-189 b sits around 20 times closer to its star than Earth does to the Sun, and completes a full orbit in just 2.7 days. Its host star is larger and more than 2000 degrees hotter than the Sun, and so appears to glow blue. “Only a handful of planets are known to exist around stars this hot, and this system is by far the brightest,” says Monika Lendl of the University of Geneva, Switzerland, lead author of the new study. “WASP-189b is also the brightest hot Jupiter that we can observe as it passes in front of or behind its star, making the whole system really intriguing.”

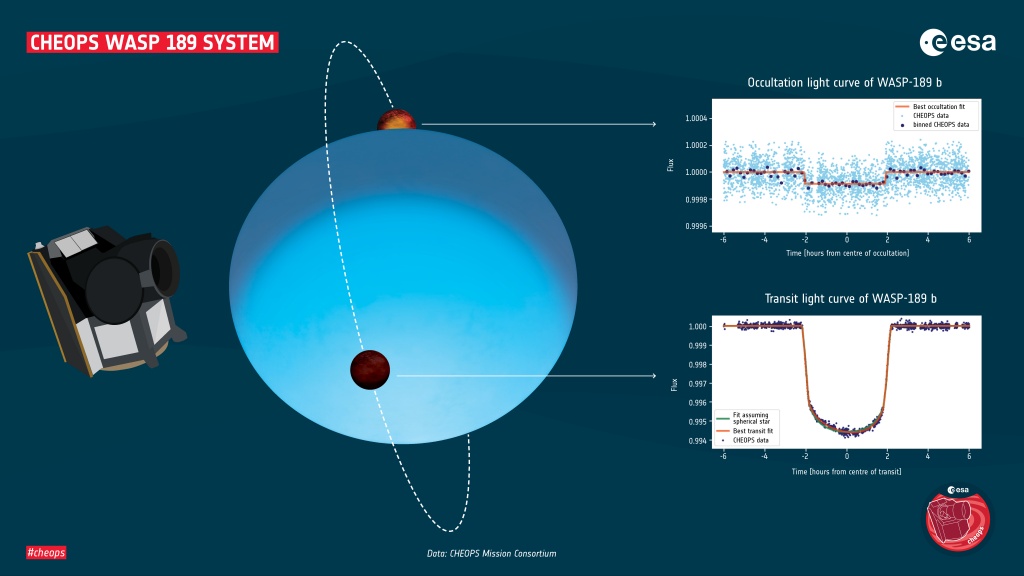

First, Monika and colleagues used Cheops to observe WASP-189 b as it passed behind its host star – an occultation. “As the planet is so bright, there is actually a noticeable dip in the light we see coming from the system as it briefly slips out of view,” explains Monika. “We used this to measure the planet’s brightness and constrain its temperature to a scorching 3200 degrees C.”

This makes WASP-189 b one of the hottest and most extreme planets, and entirely unlike any of the planets of the Solar System. At such temperatures, even metals such as iron melt and turn to gas, making the planet a clearly uninhabitable one.

Next, Cheops watched as WASP-189 b passed in front of its star – a transit. Transits can reveal much about the size, shape, and orbital characteristics of a planet. This was true for WASP-189 b, which was found to be larger than thought at almost 1.6 times the radius of Jupiter.

“We also saw that the star itself is interesting – it’s not perfectly round, but larger and cooler at its equator than at the poles, making the poles of the star appear brighter,” says Monika. “It’s spinning around so fast that it’s being pulled outwards at its equator! Adding to this asymmetry is the fact that WASP-189 b’s orbit is inclined; it doesn’t travel around the equator, but passes close to the star’s poles.”

Seeing such a tilted orbit adds to the existing mystery of how hot Jupiters form. For a planet to have such an inclined orbit, it must have formed further out and then been pushed inwards. This is thought to happen as multiple planets within a system jostle for position, or as an external influence – another star, for instance – disturbs the system, pushing gas giants towards their star and onto very short orbits that are highly tilted. “As we measured such a tilt with Cheops, this suggests that WASP-189 b has undergone such interactions in the past,” adds Monika.

Monika and colleagues used Cheops’ highly precise observations and optical capabilities to reveal the secrets of WASP-189 b. Cheops opened its ‘eye’ in January of this year and began routine science operations in April, and has been working to expand our understanding of exoplanets and the nearby cosmos in the months since.

“This first result from Cheops is hugely exciting: it is early definitive evidence that the mission is living up to its promise in terms of precision and performance,” says Kate Isaak, Cheops project scientist at ESA.

Thousands of exoplanets, the vast majority with no analogues in our Solar System, have been discovered in the past quarter of a century, with many more to come from both current and future ground-based surveys and space missions.

“Cheops has a unique ‘follow-up’ role to play in studying such exoplanets,” adds Kate. “It will search for transits of planets that have been discovered from the ground, and, where possible, will more precisely measure the sizes of planets already known to transit their host stars. By tracking exoplanets on their orbits with Cheops, we can make a first-step characterisation of their atmospheres and determine the presence and properties of any clouds present.”

In the next few years, Cheops will follow up on hundreds of known planets orbiting bright stars, building on and extending what has been done here for WASP-189b. The mission is the first in a series of three ESA science missions focusing on exoplanet detection and characterisation: it has significant discovery potential also – from identifying prime targets for future missions that will probe exoplanetary atmospheres to searching for new planets and exomoons.

“Cheops will not only deepen our understanding of exoplanets,” says Kate, “but also that of our own planet, Solar System, and the wider cosmic environment.”

Images

Notes for editors

‘The hot dayside of WASP-189 b and its gravity-darkened host star seen by CHEOPS’ by M. Lendl et al. appears in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

More about Cheops

Cheops is an ESA mission developed in partnership with Switzerland, with a dedicated consortium led by the University of Bern, and with important contributions from Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the UK.

ESA is the Cheops mission architect, responsible for procurement and testing of the satellite, the launch and early operations phase, and in-orbit commissioning, as well as the Guest Observers’ Programme through which scientists world-wide can apply to observe with Cheops. The consortium of 11 ESA Member States led by Switzerland provided essential elements of the mission. The prime contractor for the design and construction of the spacecraft is Airbus Defence and Space in Madrid, Spain.

The Cheops mission consortium runs the Mission Operations Centre located at INTA, in Torrejón de Ardoz near Madrid, Spain, and the Science Operations Centre, located at the University of Geneva, Switzerland.

For more information, visit: https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Cheops

For further information, please contact:

Monika Lendl

University of Geneva, Switzerland

Email: monika.lendl@unige.ch

Kate Isaak

ESA Cheops project scientist

Email: kate.isaak@esa.int