Memories of Europlanet’s Birth

Michel Blanc (Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Planétologie (CNRS-University of Toulouse-CNES), France), Coordinator of the European Planetology Network (2005-2008) and the Europlanet Research Infrastructure (2009-2012) looks back on the origins and evolution of Europlanet.

Read article in the fully formatted PDF of the Europlanet Magazine.

Origins

At the start of the 21st Century, planetary science in Europe was entering a ‘golden age’. European scientists were involved in all the major missions to the Solar System.

In particular, the ground-breaking Cassini-Huygens mission to the Saturnian system demonstrated that European partnership could create science that went way beyond anything any individual country could generate on its own.

Europe already had the European Space Agency (ESA), with its origins in the 1960s. What it lacked, however, was an organisation that would enable it to exploit the scientific data that ESA-supported missions were generating to the fullest extent. And it needed something that would enable European citizens to fully appreciate the contribution that Europe was making to the exploration of our Solar System, its planets, moons, comets and asteroids – and even of other planetary systems beyond ours – and the opportunities that they too had to become part of this great age of voyage and discovery.

Europlanet was born as a result of heated and enthusiastic discussions around 2002-03, during the seven-year journey to Saturn and Titan with Cassini-Huygens. As members of the Project Science Group (PSG) of the Cassini-Huygens mission, American and European scientists and engineers were working together, hand-in-hand, on plans to tour the ‘Lord of the Rings’ and produce the wonderful science they had dreamed of for two decades.

European scientists were involved in nearly all the 16 instruments of the mission – but as representatives of individual European nations, and not of the continent as a whole. Although Europeans were nearly equal by number to our American colleagues, mission preparation and data analysis work were funded by one single agency, NASA; European contributions to scientific analysis came from different national agencies, without a consistent framework for this major European undertaking in space – except for the ESA-led Huygens probe itself.

A few of us on the European component of the Cassini-Huygens team, including David Southwood, who was the Principal Investigator of the Cassini magnetometer instrument, and Daniel Gautier who had dreamed for many years of seeing the emergence of a united European planetary science community, realised that this ‘fragmentation’ of our scientific activities and of their funding threatened to weaken the overall science produced, and decreased its profile in the eyes of European citizens. We knew exactly what united us and could make us work together: the science programme of ESA (Horizon 2000+ at the time, soon to be followed by Cosmic Vision), which promised to take us to all provinces of the Solar System – and even beyond, to the expanding family of exoplanets. But we also knew that ESA was not in a position to fund the data analysis of the beautiful missions it was flying.

In this context, only one institution could help us complement the national resources and produce the great science return that the ESA science programme deserved: the European Union (EU).

Shaping Framework Programme 6 (2005-2009), and beyond

Expanding beyond the core of Cassini-Huygens scientists, a small number of us met several times between 2002 and 2004 to brainstorm on ways to seek support from the EU. Soon, a delegation of our group went to visit the scientific officer in charge of our field at the Directorate General (DG) Research office in Brussels. This meeting was instrumental in firming up our plans: it helped us identify the ‘Support to Research Infrastructures’ instrument of Framework Programme 6 (FP6) as the programme that could fund us. It also helped us to later design a proposal that would meet, not only our needs, but also the expectations of the European Commission.

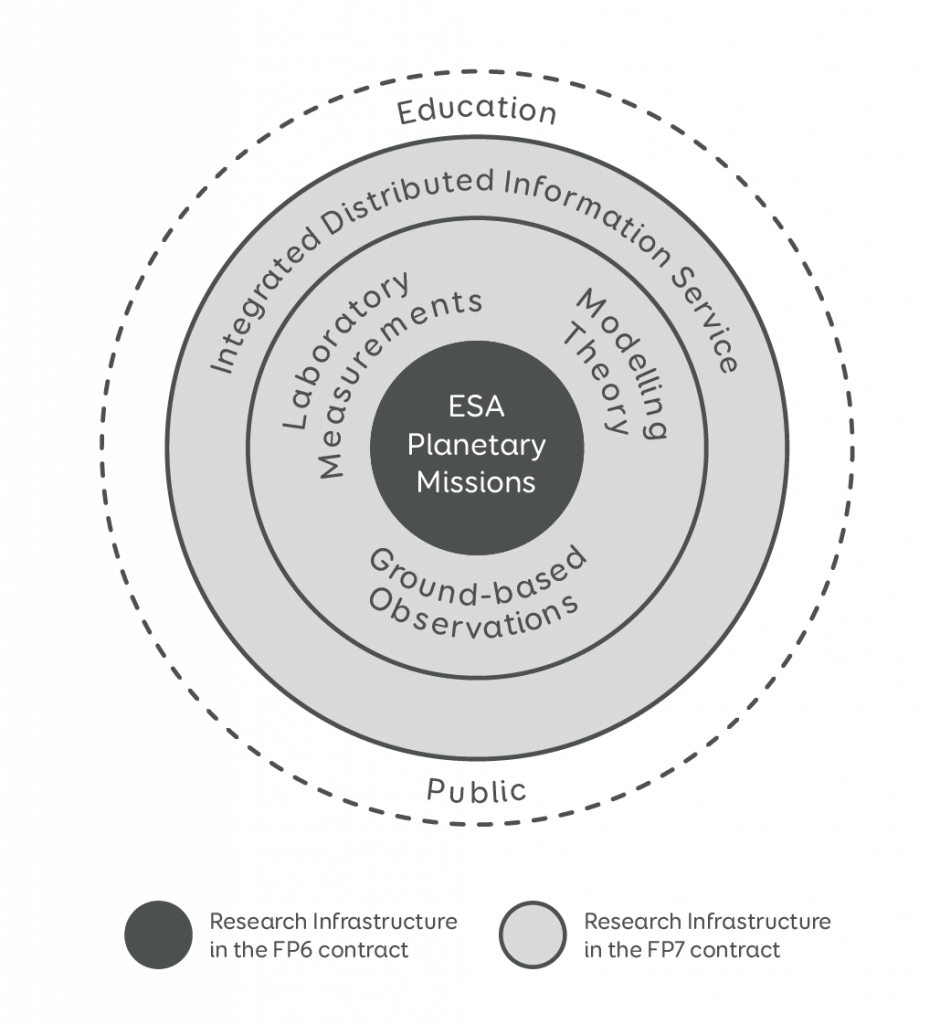

The architecture of this proposal progressively took shape during the year that separated our visit to Brussels from the submission deadline. Figure 1, adapted from one of the very first presentations of Europlanet to the community, shows the four key ideas that guided Europlanet’s design, represented as four circles.

The first idea was to gather the pan-European community of European planetary scientists around a major transnational research infrastructure: the science programme of ESA, which was from the very beginning the core of Europlanet (inner circle). The second idea was that planetary science is not only fed by space observations: ground-based observations, modelling, theory and laboratory experiments play an equally important role and help maximise the science return of space missions; this is the ‘second circle’ of Europlanet. The third idea was that European scientists needed an efficient, web-based data-sharing and data-mining tool, the equivalent of a Virtual Observatory for planetology, to take full advantage of their shared infrastructure. This tool, called the ‘Integrated and Distributed Information Service’ (IDIS), which at the time existed only in our minds, was to be the ‘third circle’ of Europlanet.

Finally, one of our strongest motivations was to share with the European public and each national education system the science and benefits produced by European planetary missions. This ‘public engagement’ was to be the fourth circle of Europlanet.

Following a key meeting of the proposers on the occasion of the EGU general assembly in Nice in 2003, the first Europlanet proposal was successfully submitted to the European Commission as a Coordination Action.

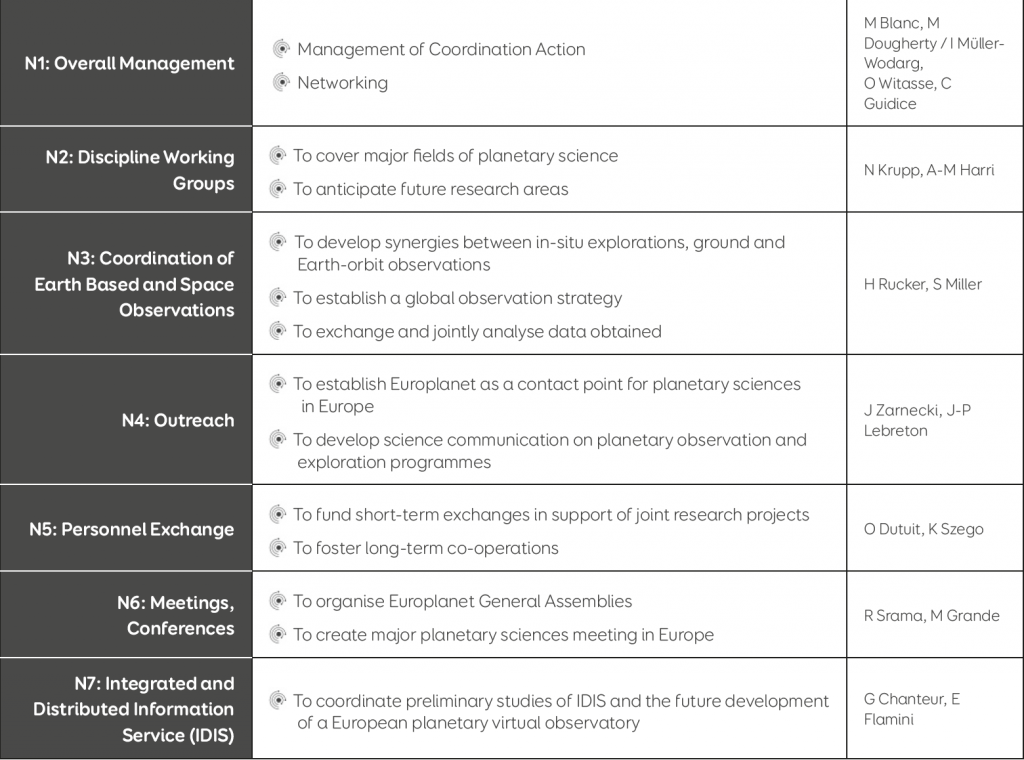

Its seven networking activities (Table 1) were designed to implement the different elements shown in Figure 1 and their connection to the ESA science program. With a two-million Euro budget, it was a modest first step, but one that prepared what was to be a regular expansion and consolidation of Europlanet at each of its successive renewals.

With the next step four years later, under Framework Programme 7, Europlanet was successfully expanded into a full multi-faceted Research Infrastructure linking the first three circles of Figure 1 (space and ground-based observations, laboratory work, numerical simulation and the development and operation of a future Virtual Observatory for planetary scientists) with a significantly larger budget of 6 million Euros for the 2009-2013 period.

Echoing its origins, the first month of Europlanet’s life, in January 2005, coincided with the successful landing of the Huygens probe on Titan, the first-ever landing of a space vehicle on a giant planet’s moon. The cameras of Huygens revealed a surprisingly Earth-like world under the thick cover of Titan’s clouds and confirmed Europe’s outstanding place in the exploration of the Solar System. Jean-Pierre Lebreton, Huygens project scientist and an active member of the first Europlanet proposal team, appeared on the ESOC screens on 14 January 2005, just after the first signal had been received from the probe, to emotionally announce “we heard the baby crying”.

It was at this moment Europlanet, in our hearts, was truly born too!