Planetary Perspectives

Henrik Hargitai is a planetary geomorphologist and media historian. He is a professor of planetary geomorphology, planetary cartography, typography and media history at Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), Budapest, Hungary and has a PhD in Earth Sciences and Philosophy (Aesthetics). He is the editor of the Pocket Atlas of Mars 36.

Read article in the fully formatted PDF of the Europlanet Magazine.

What was the first map that you created?

When I was really young, I made a Lord of the Rings-like map. Then, at high school, I made a poster of paleogeographic maps that was exhibited in the school corridor.

Who are your mapping inspirations?

When I was a student, around 1999, I wanted to have an atlas of the Solar System. I searched on the Internet and found a Russian atlas. I contacted the authors via email and to my surprise Kira Shingareva, who edited the atlas, invited me to Moscow. I was shown around the MIIGAiK University in Moscow, where the atlas was created. They had a project making a series of multilingual planetary maps, and I became the editor of its Central European edition.

How have you reached your current job position?

Like many other planetary scientists, I started as an intern at the Lunar and Planetary Institute where Paul Schenk introduced me to planetary science. When I came back to Hungary, I moved away from terrestrial geography towards planetary geography. In 2015, after 20 years of teaching at ELTE University, Budapest, I had the opportunity to work with Ginny Gulick at the NASA Ames Centre to map channels near Hellas Basin on Mars. Now I’m back in Hungary.

Why a Pocket Atlas of Mars?

Because I don’t like screen maps and wanted to have a proper, map-like map of Mars that I can hold in my hands. I love browsing maps, old and new, for hours sometimes. That’s much better than travelling on Street View. Perhaps I’m nostalgic because my examples were the atlases I had in the 1980s, when I was young, from A6-sized pocket maps of Hungary to A3-sized world atlases.

How long did the Atlas take you to put together?

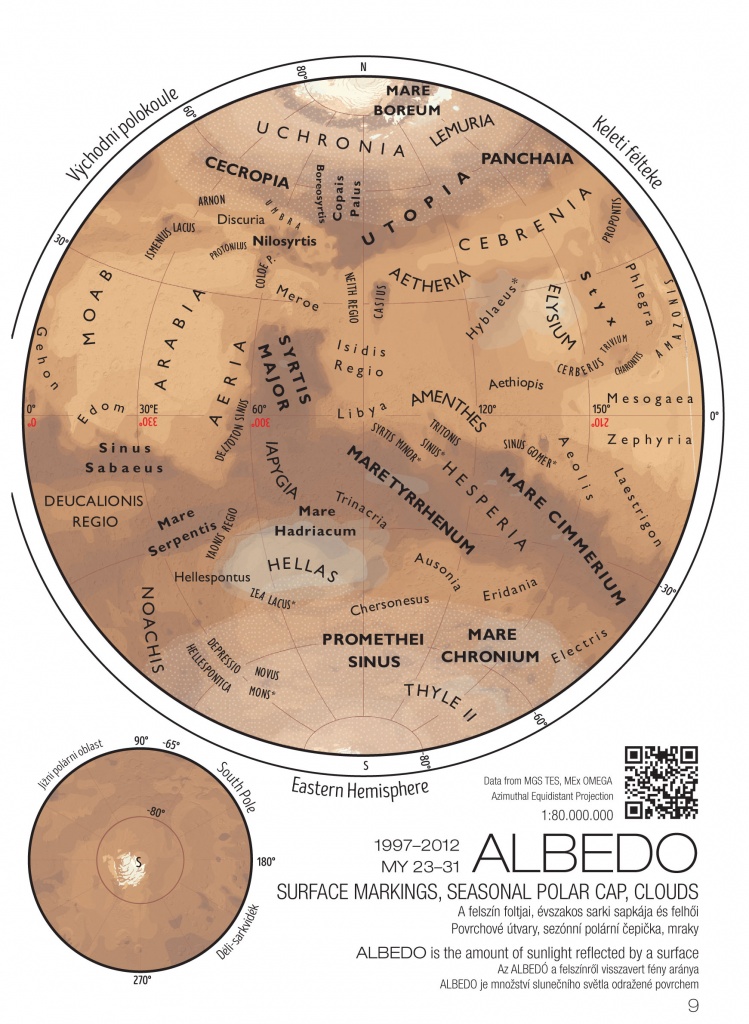

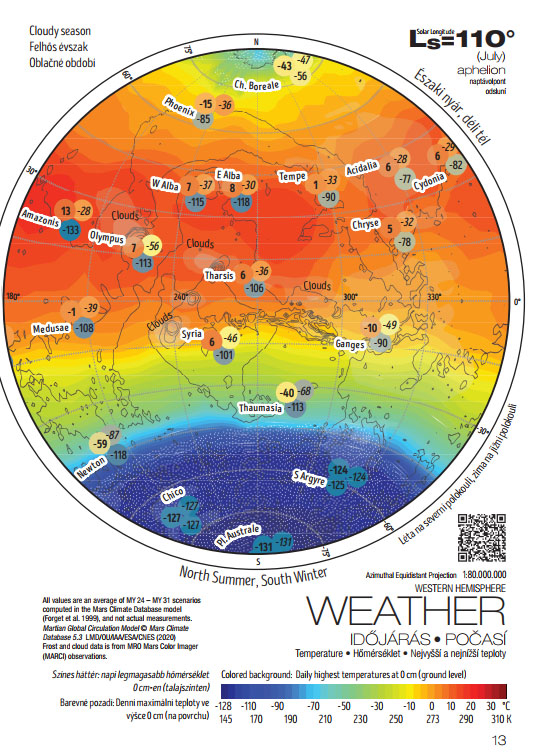

A very long time! In 2011, I started editing the Encyclopedia of Planetary Landforms, and I created distribution maps for many landforms. Then I started preparations in 2016 at NASA, where I collected catalogues of surface landforms. By 2020 I had most of the data in hand. The actual full-time work started in the summer of 2020 at the foot of the Sümeg hill, during a two-family holiday, where I made the albedo map. Then I made the calculations for the climate maps in cafés in Budapest.

Where on Mars do you find most interesting, as a mapper?

It is always those regions that I studied and mapped in detail. I studied channels that were not mapped before: in north east Tharsis and north east Hellas. You could say that I ‘lived’ for a year in each site because I spent eight hours per day mapping those places.

Any unexpected outcomes from the Atlas?

When I developed the climate diagrams, I realised that Mars is more Earth-like than I previously thought. But also more alien because of its vast history imprinted into the surface we see today. I also realised that what I am really looking for in making these maps is to get a little closer to understanding if Earth is a ‘normal’ planet, which we still don’t know. You get to know yourself by looking at others. Mars is the best known ‘other’ we can compare our planet to. It is an alien planet: its surface is old and yet geologically ‘primitive’, not like the Earth. But is it a ‘normal other’?

What’s your next project?

This was an outreach project but professional scientists also need maps like this for their planetary mapping projects. First of all, we need more planetary cartographers and we need planetary geographic maps. I think geographic maps are an important future direction in planetary mapping because these maps are the best tools to communicate planetary discoveries and generally our geo-knowledge. One of my former professors of literature wrote to me that she knew Mars is ‘rugged’ but never thought it would be rugged like this.

For professional work, we need a digital geographic information system (GIS) with thematic layers. I know some 60 catalogues of features scattered in the literature. The next project is to collect those catalogues and merge them into a Mars GIS, which could be used as a reference GIS for Mars. But the real next project is to emerge from the pandemic with my family as healthy as possible.